Gode Cookery Presents

True stories, fables and anecdotes from the

Middle Ages

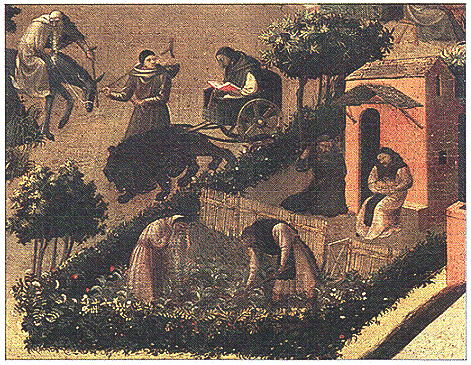

MONASTIC GARDENS

The inhabitants of monastic houses were among the most diligent of Medieval gardeners. It is told in Genesis, the first book of the Old Testament, that God created a garden in Eden, a lovely place with multitudes of plants and trees. Adam and Eve's sin of disobedience which caused their exile became for Christians the Doctrine of the Fall of Humanity, and the tradition grew in succeeding human generations that one avenue for seeking associaiton with God was by gardening. An obvious venue for spiritual gardening was the monastery. The monastic rule of St. Benedict, drawn up in the sixth century for his community at Monte Cassino in Italy, was profoundly influential in England, and the Benedictine Rule specifically enjoined the cultivation of gardens. Any monastery, Benedictine or otherwise, would require a kitchen garden, or gardens, depending on the size of the house. The kitchen garden would probably lie within a hedge or wall and would produce peas and beans required for the daily pottage, together with leeks, onions, and garlic. Larger gardens might also produce apples and other fruits, have beehives for the production of honey, and grow hemp. Hemp (cannabis) was introduced into England by the Romans, not as a drug but for the making of rope and canvas, and was for this reason vital to a useful Medieval industry. The garden for a monastic infirmary would probably have been smaller than the kitchen garden and more specialized. Here would have been grown the ingredients required for medicine, salves, and tonics. The modern word "drug" is derived from the Old English verb "driggen" meaning to dry, reflecting the preparation undertaken by the infirmarer of the herbs that he would store for use in his service to the sick. The infirmary garden at Westminster Abbey covered an acre, and would have offered space for convalescents to stroll among the beds of assorted herbs and flowers grown for their medicinal properties while enjoying gentle exercise in scented air. It may be noted in passing that the substantial garden maintained by the cellarer of Westminster Abbey was at a distance from the main buildings of the abbey at a location now known as Covent Garden, from the Norman French "Le Couvent" or "The Convent," while the orchard of the abbey is memorialized by Abbey Orchard Street.

In London by the reign of

Edward I there existed a nursary trade

to supply the needs and desires of gardeners. One could buy such things

as seeds of leeks, mustard, hemp, colewort, and onions, as well as

onion

sets, other small plants, and grafted fruit trees. An organized nursary

trade was also appearing around the same time in such places as Oxford,

Norwich, and York. Itinerant seedsmen moving about from place to place

with their packhorses filled in the gaps between organized commercial

centres.

A trade in the surplus produce of household gardens also existed. One

market

for such surplus and for the produce of market gardens in the later

Middle

Ages was in London in front of the church of St. Augustine, Watling

Street,

close to St. Paul's churchyard.

Pleasure gardens, too, were

a feature of some monasteries, planted

with trees, shrubs, and vines. The cloister garth of a monastery would

commonly be planted with trees, herbs, and flowers to make them more

pleasant

for contemplative recreation. Even more appropriate to contemplation

would

have been a paradise, inspired by the Garden of Eden described in

Genesis

2:8-9. It was the custom that paradises were enclosed and used for

prayer

and meditation. The sacrist of the monastery saw to it that the

paradise

produced the flowers needed to decorate the church for various

occasions,

and such devotional flowers as roses and lilies would certainly have

been

grown there. When a monastery was able to establish a paradise, it was

usually placed beside the monk's cemetery, normally north of the

church,

and itself decorated with trees, flowers, and fountains, together with

a central cross or crucufix. Even heads of monastic institutions

sometimes

established private gardens, which reflected personal tastes and

interests

in favourite fruit trees, shade-giving trees, herbs, flowers, or

vegetables.

CARTHUSIAN GARDENING

The cloistered religious

orders of England made an ongoing contribution

to the tradition of gardening, but among the monks and nuns a special

niche

in the history of English Medieval gardening was filled by Carthusian

monks.

Because of the disciplined nature of their lives all Carthusians were

gardeners.

The Carthusian Order began in 1084 when Bruno, a priest and head of the

cathedral school and chancellor of the diocese of Rheims, in his mature

years founded the Grande Chartreuse in Provence. In Carthusian houses,

or charterhouses as they were called in England, the monks lived lives

of strict asceticism and solitude, each one residing in a separate

cell,

very much like a private house, within the monastery precincts. The

brethren

gathered each day to participate in collective worship, but they ate

together

only on important feastdays. They followed a common daily schedule, but

lived essentially as recluses. They prayed, studied, ate, and worked

for

the most part within the small world of their cells and gardens, each

one

following his own programme of cultivation.

Pleasures and Pastimes in Medieval England. Compton Reeves. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. |